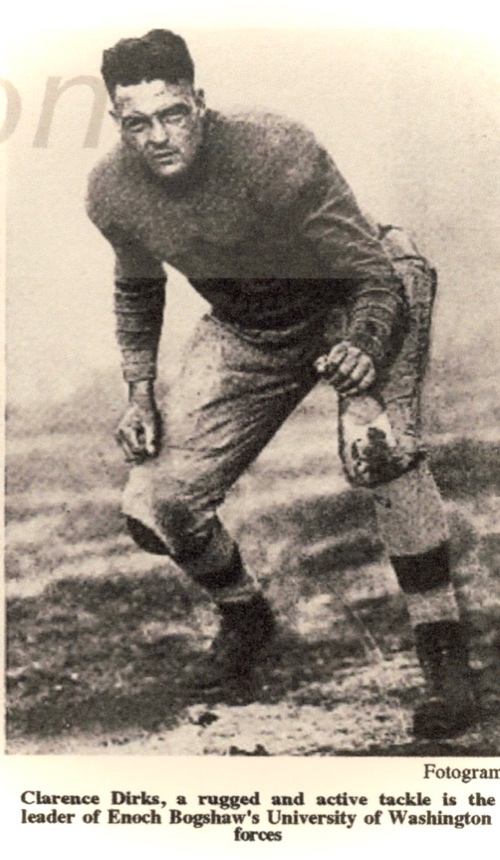

Clarence Dirks

A Man for All Seasons – A Husky to the Core

Dan Brown’s The Boys in the Boat was on the New York Times bestseller list for over two years. It tells the fascinating and now well-known story of the 1936 Olympic victory by the UW crew as well as the personal sagas of its members. Brown’s prose is compelling, often riveting, yet perhaps the most memorable passage from the book was not written by the book’s author at all but rather was a line he quoted written by a Seattle journalist:

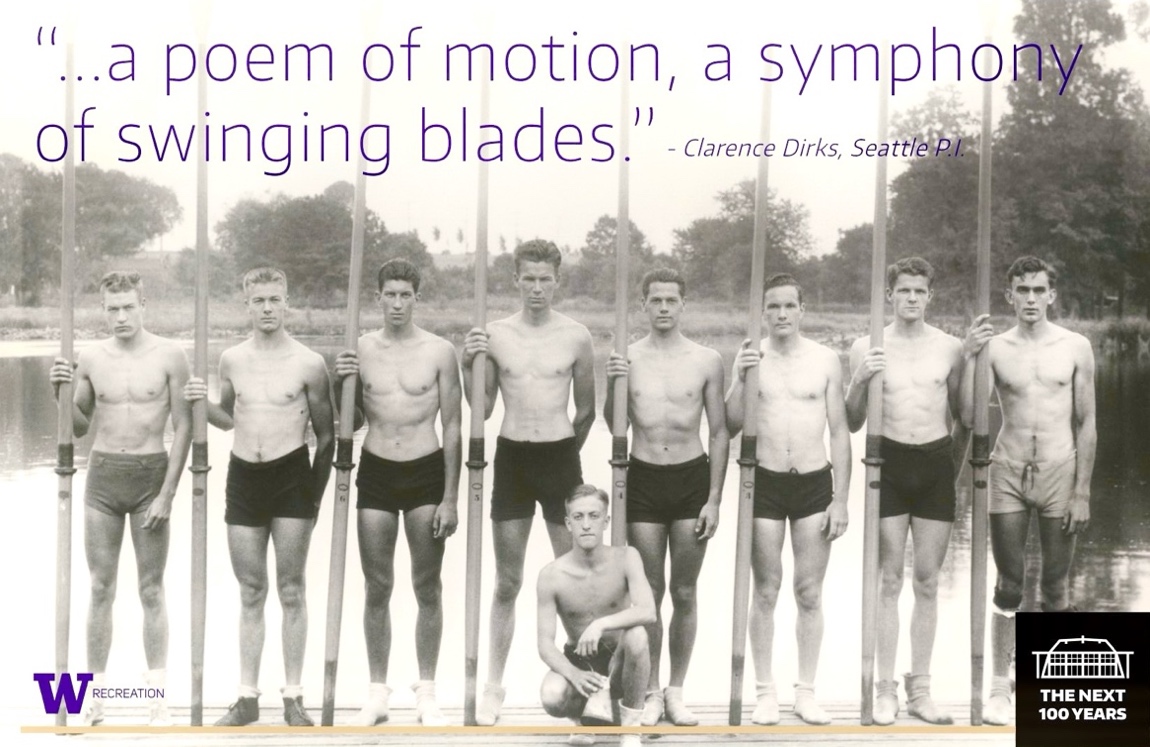

“It would be useless to try to segregate outstanding members of Washington’s varsity shell, just as it would be impossible to try to pick a certain note in a beautifully composed song. All were merged into one smoothly working machine; they were, in fact, a poem of motion, symphony of swinging blades.”

Clarence Dirks, Seattle PI, 1936

If you visit the century old ASUW Shell House, you’ll find a banner with the last part of that quote hanging from the ceiling. Perhaps you’ll pick up a brochure celebrating the Shell House and solicitating donations for its restoration and discover this photo of the 1936 crew:

Finally, if you’ve seen the excellent 2017 PBS documentary, The Boys of ’36, you may recall that that same quote was cited in describing the magic that propelled coach Al Ulbrikson’s team to an improbable victory in a hostile environment.

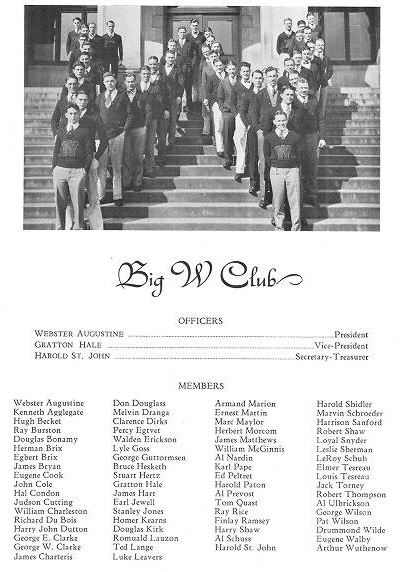

The quote in question was penned by my father, Clarence Dirks, whose association with the UW athletic program went far beyond his coverage of the UW crew in 1936. In his 13 years as a Seattle Post-Intelligencer sport writer, he covered the full gamut of UW sports. Prior to that he was a full-season UW football captain as both a freshman and a senior. He played in the Rose Bowl against Alabama (a one-point Husky loss) and a few years later played on the first varsity-alumni football game (won handily, 33-13, by his alumni team). He collaborated with Al Ulbrickson and George Pocock on magazine articles in Esquire, The Saturday Evening Post, and Ken which brought national attention to the UW crew program.

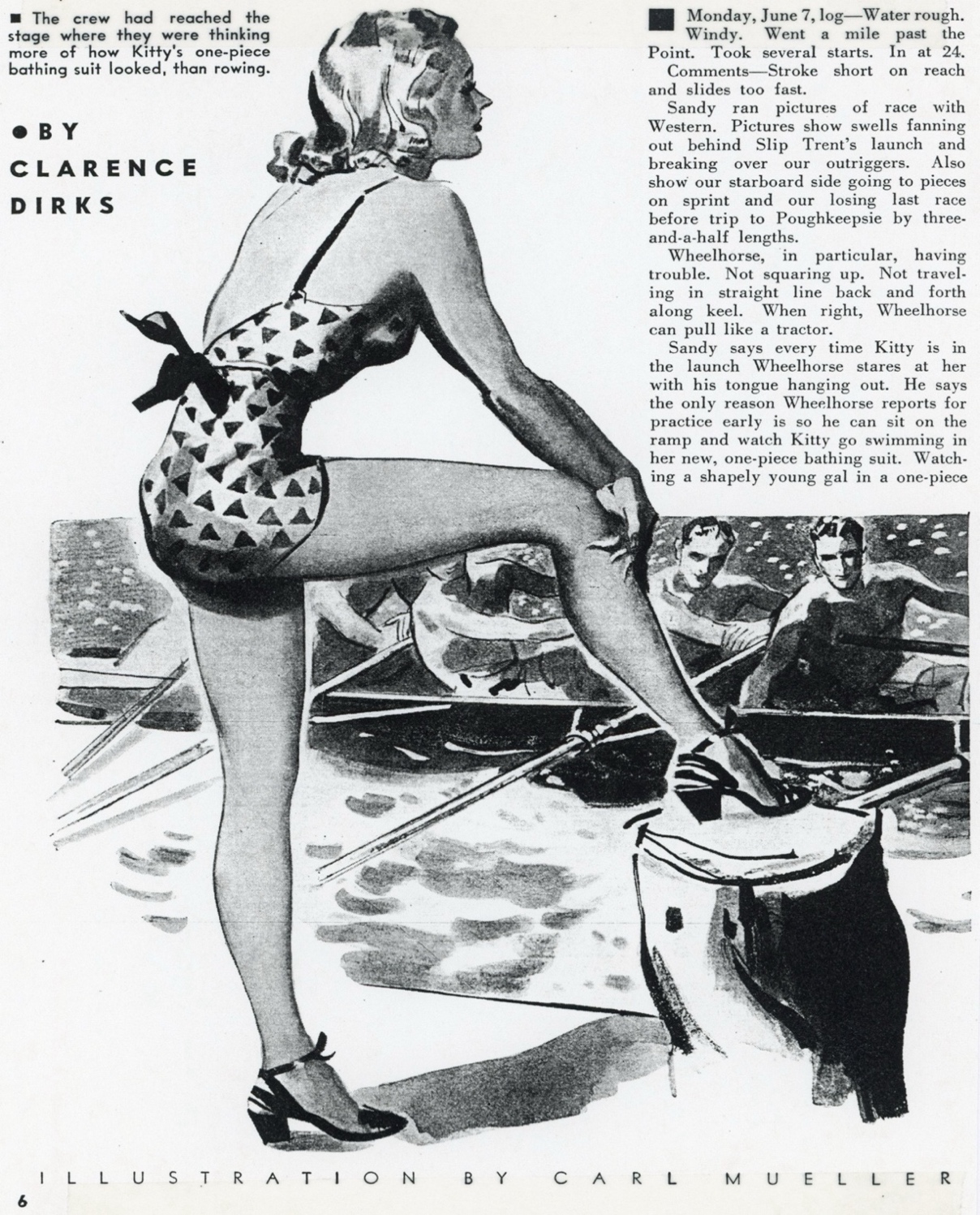

Dad also penned fiction articles drawn from his experiences with both the UW football and crew programs which appeared in Dime Sports, The All-America Sports Magazine, and College Humor. Dad’s story “Poughkeepsie Pluck” (Dime Sports, June 1936) pivoted around a fictionized version of Al Ulbrickson’s legendary performance stroking the Washington varsity to victory with a torn arm muscle in 1926, the same year both Dirks and Ulbrickson were members of the Big W club. (Photo from Tyee yearbook)

His September 1938 article in College Humor, “Varsity Log,” told a fictional tale of a girl who had a very disruptive effect on the practice sessions of a college crew. Whether this was based on coach Ulbrickson’s Washington varsity is unknown. In any event the original of the illustration shown on the first page of that article has a place of honor in my home office.

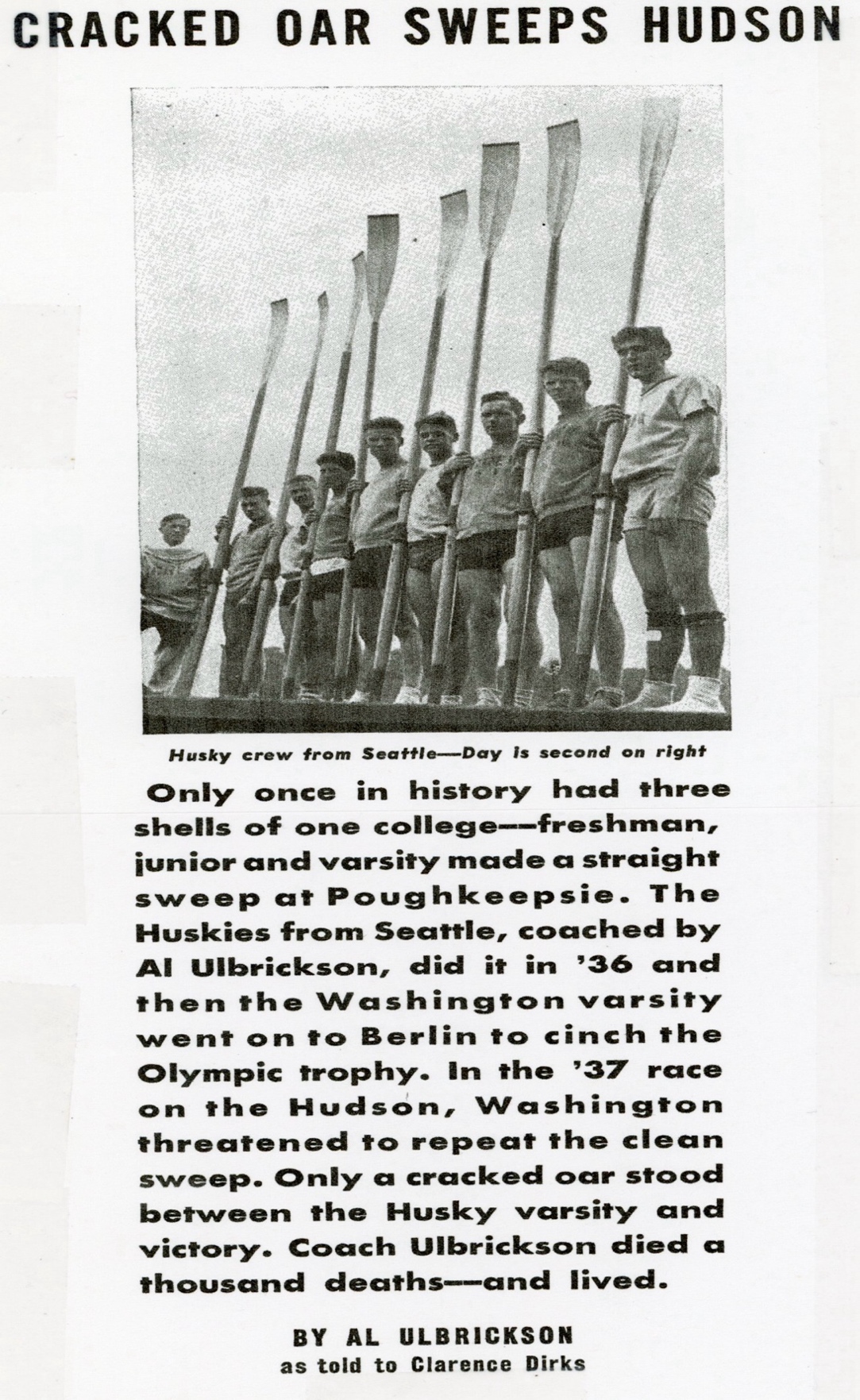

Ken was a short-lived, large format magazine with full page photo spreads, similar in appearance to Life and Look but with many more controversial and political articles. Ernest Hemmingway was a frequent contributor. Clarence Dirks and Al Ulbrickson collaborated on the July, 1938 piece “Cracked Oar Sweeps Hudson.”

Besides telling the tale of Washington’s repeat victory in the 1937 Poughkeepsie Regatta despite rower Charley Day’s cracked oar, the article also relates Ulbrickson’s unexpected lucky number in the previous year’s Olympic Games:

“I thought of all the curious superstitions in rowing. I thought how the previous season—1936—13 had been my lucky number, or must have been because, previous to winning in Germany, our suits had been sent east in trunk number 13. The train car was number…13. Thirteen were in our party which embarked for Berlin. Arriving in Hamburg, we entered Germany through warehouse gate marked number…13. The bus which took us from Berlin to the police officers’ training school in Grunau was number…13. At the official opening of the games my wife sat in seat number…13. The day of the rowing finals was the first day of my 13th year of marriage. And now there was a 13-minute delay in the all-important race.”

Coach Al Ulbrickson about to bark orders to his varisty eight at Poughkeepsie, New York.

Seventy-five years after the Husky’s epic victory against Italy and Germany in Berlin another race involving Joe Rantz and his teammates was taking place. But this time the combatants were unaware of each other, at least at first. For at the same time that published author Daniel James Brown was researching material for The Boys in The Boat, an aspiring author, former college oarsman for Columbia and newly hired university professor, Michael Socolow, was doing the same thing. And Socolow struck first with an article, “Six Minutes in Berlin,” published by the online magazine Slate in July, 2012. It’s an exciting read. The article caught the attention of publishers who had initially rejected his idea for a book on the same topic.

But, unfortunately for Socolow, Brown’s book was almost complete at that point and was published to instant acclaim a year later. No publisher would touch professor Socolow’s proposed book now. Discouraged, but undeterred, the young academic realized he had to write a book more attuned to the research community rather than the general reader. The result, Six Minutes in Berlin: Broadcast Spectacle and the Nazi Olympics, focused on both Ulbrickson’s crew and the events leading up to the big race but also the history of radio, an evolving media at that time. Personally, I find it an equally engaging read though I’m sure it added more to the author’s advancement through academia than to his pocketbook. And I might be just a little prejudiced after exchanging a few emails with Mike Socolow which included the glowing comment:

“Your father was a legend in Seattle sports history, with his reporting and radio program, and he was up there with George Varnell and Royal Brougham as the big names that were known nationally for their work.”

Of course, Royal Brougham, my dad’s boss and mentor during his tenure at the Seattle PI, is a Seattle print and broadcasting legend. Varnell was an accomplished sports writer for the Seattle Times as well as longtime football referee. In fact, while my dad played tackle for the Washington side in that famous 1926 UW versus Alabama game, Varnell was on the field as an official. Varnell had also been a football star during his college days playing under Amos Alonzo Stagg at Chicago and later at Kentucky. And, amazingly, before joining the Seattle Times sports staff, Varnell was for a short time the head coach of the then Gonzaga College basketball and football teams while working for a Spokane daily paper. While covering the UW crew team, both my dad and George Varnell rowed under Ulbrickson to get a “feel” for crew. Whether they ever got into a shell together, or competed informally, is unknown.

Clarence Dirks was born in 1903 in Oakland, California, the first of five children. The family later moved to Palo Alto and subsequently to the Butchertown neighborhood of San Francisco. As a boy, he helped his father deliver ice up and down the city’s hills in a horse-drawn cart before heading off to school. Clarence’s great-grandfather, John Johnson Dirks, arrived in San Francisco around 1850 from Holland. He was the shipwright on a German sailing ship that probably took five or six months to make the journey around Cape Horn.

By 1868 John J. Dirks had established the first shipyard in the India Basin neighborhood of the city where he and his sons built scow schooners which hauled hay, grain, salt and other commodities from otherwise inaccessible places upriver. Today, a new waterfront park is being created from the Dirks’ boatyard. The cottage the family built in 1875 (San Francisco Landmark #250) is being transformed into a visitor center.

From 1921 to 1924 Clarence attended Palo Alto high school (Paly) where he won 12 varsity letters and was selected by his former coach as the greatest athlete ever to attend the school a quarter century later:

“Clarence Dirks, star tackle and captain of the Palo Alto High School football team of 1923, was today voted the greatest athlete to ever compete for the local school. Dirks led a lengthy list of candidates in the selection made by Howard “Hod” Ray veteran Palo Alto athletic director and coach…The veteran coach in naming Dirks recalled that his former tackle was a big, rough 200 pounder who was head and shoulders over any lineman in the league in his days. He has also a star performer in basketball, baseball and a standout javelin man on the track team.”

(Palo Alto Times, April 5, 1950)

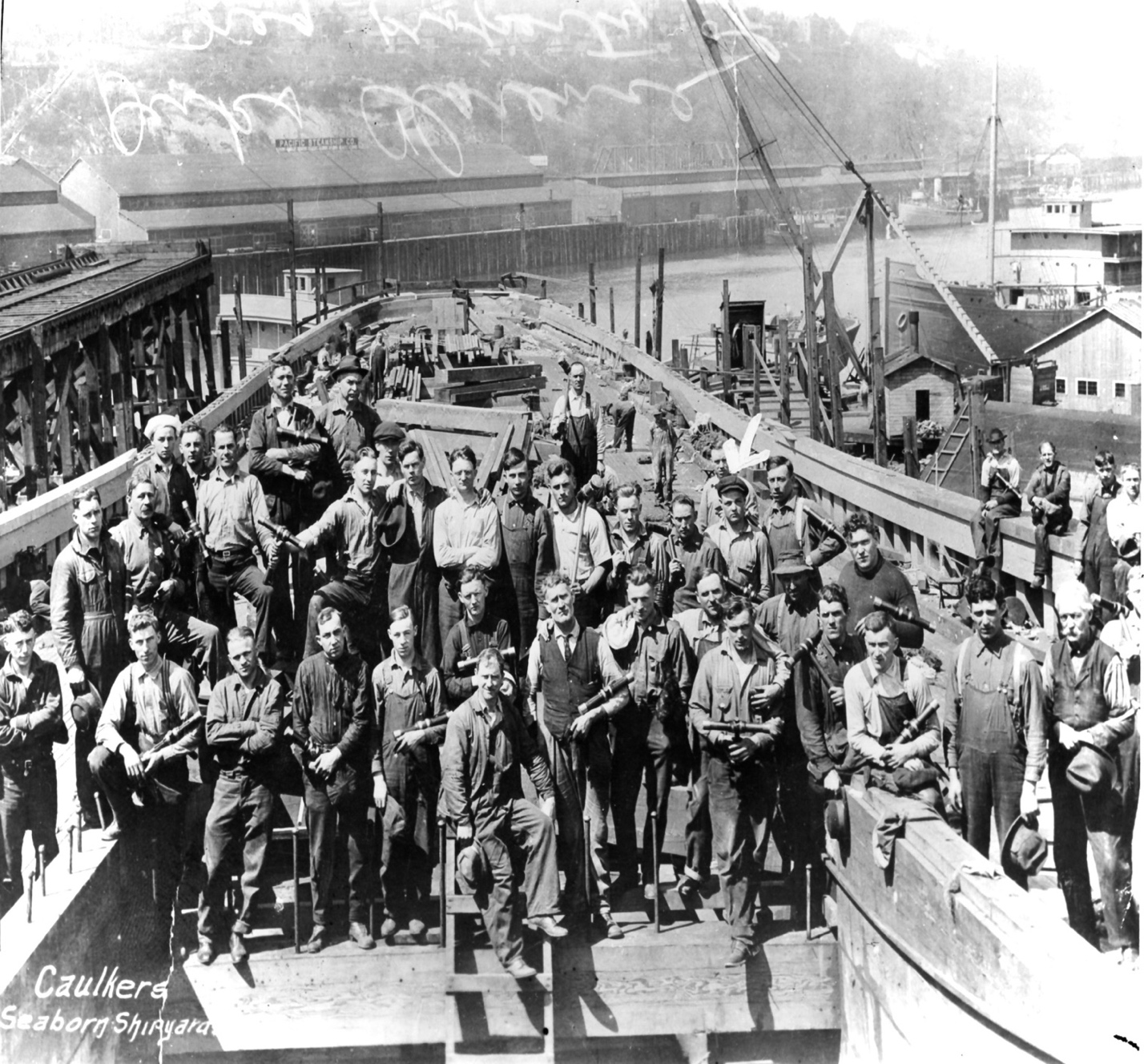

Now, what exactly made Clarence Dirks such an outstanding athlete at Paly and later at the University of Washington? What preparation had allowed him to excel to the extent that he did? There were no training rooms, exercise equipment or specialized strength coaches in those days. The answer has to do with the outbreak of World War I in 1914 in Europe. Almost immediately the ailing US ship building industry started to revive. Clarence’s father George O. Dirks was finally able to return to the trade he had apprenticed in a decade earlier. George no longer had to deliver ice, try to eke out a living as a dairy farmer or take tickets at a Nickelodeon as he was currently doing. The elder Dirks had been offered a ship caulking job in Washington State and the family soon moved there. Clarence finished eighth grade in 1917 in Aberdeen just after the US entered the war. He decided to interrupt his education and apprentice at the Seaborn Shipyards in Tacoma where his father had become boss caulker. It was serving his 18-month apprenticeship there and later on the Seattle waterfront and back home in San Francisco that Dirks not only gained muscle and the sharp eyesight needed to avoid industrial accidents, but also learned much about the art of leadership and an ability to get along with the diverse set of backgrounds and personalities found among his shipyard workmates. What he learned in his three-year break from formal schooling would serve him well for the rest of his life.

This photo shows the ship caulking crew at the Seaborn Shipyard in Tacoma, Washington in 1917 during World War I. An arrow on the right points to Clarence Dirks who was serving serving an 18-month apprecticeship to the trade. The boat under construction is a Ferris-tyupe schooner. (Seaborn Shipyard Photo)

Clarence Dirks spent three years as a ship caulker, filling seams in wooden boats to make them watertight, before starting high school in Palo Alto near Stanford University. At Paly he was active in journalism and graduated as president of his small half-year class of 25 in February, 1924. He enrolled in the University of Washington that fall, not because of its excellent football program under coach Enoch Bagshaw, but rather because a Paly coach’s wife, a UW alum, had told him that the University of Washington had the finest journalism school on the West Coast. Once on campus, he joined the Theta Beta Pi fraternity and settled into college life.

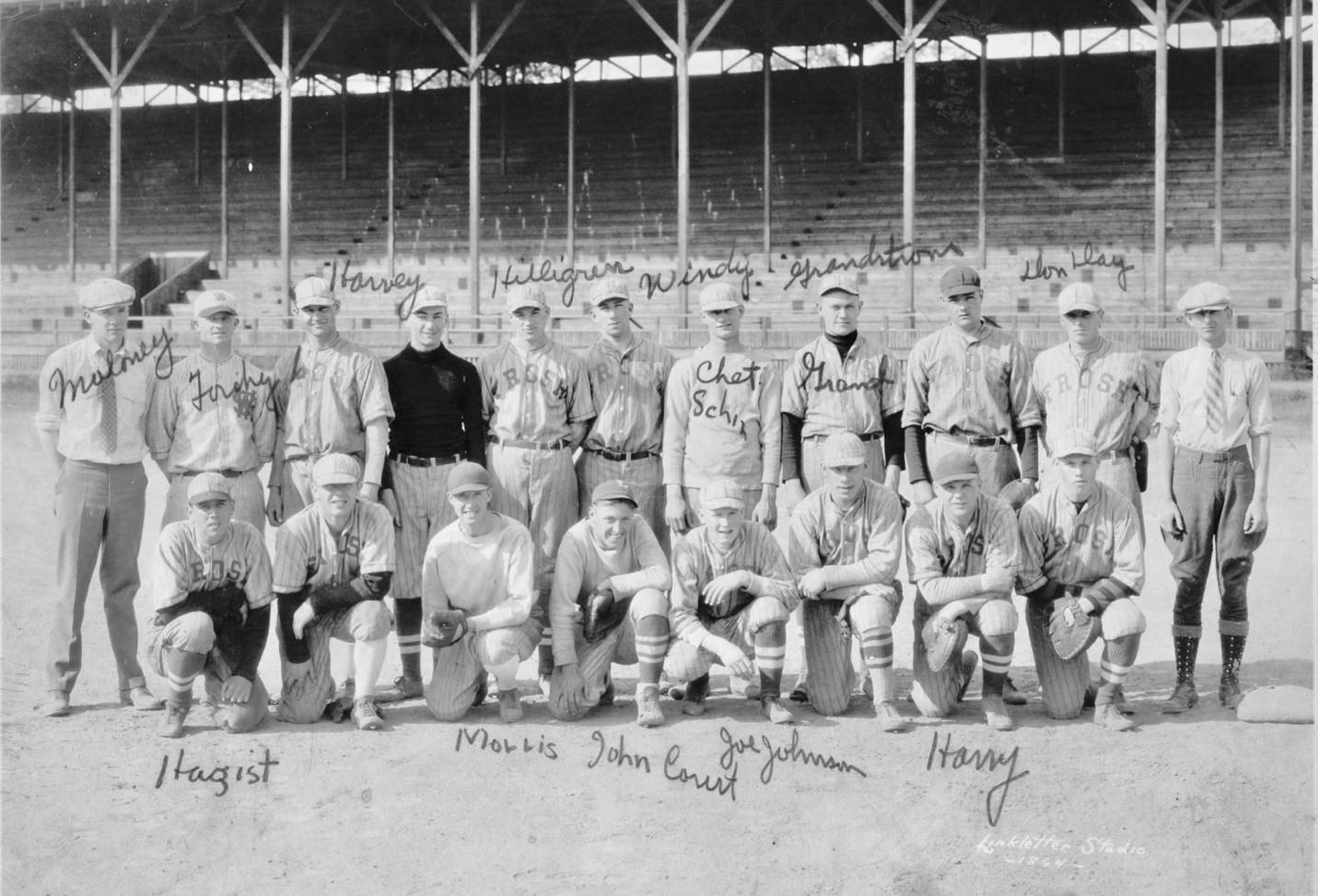

Dirks did turn out for the freshman football team that fall. He played tackle and captained the squad. In the spring he joined the freshman baseball team as a catcher.

Clarence Dirks’ freshman year at the University of Washington was a busy one. Not only was he captain of the frosh football squad, he was also a catcher on the 1925 freshmen baseball team pictured above. Dirks is to the left of Don Day in the back row. (Coach Torchy Torrence)

The following fall Clarence Dirks earned a spot on the 1925 varsity football team, one of the most renowned UW teams of all time. And one of greatest players to ever wear a Husky uniform and Washington’s first consensus All-American, George Wilson, was a teammate. The Huskies finished the regular season 10-0-1, the only blemish on their record a 6-6 tie against a formidable Nebraska eleven. The UW team had outscored their opponents 480-39 and were headed to the Rose Bowl for the second time in three seasons. After several teams refused an invitation to play Washington in Pasadena, the University of Alabama accepted. The Crimson Tide’s season had been equally impressive, perhaps even more so. With a record of 9-0, they outscored their opponents 277-7. They were only scored on once all season, that in a 50-7 victory. Much has been written about the 1926 Rose Bowl in which Alabama prevailed 20-19 over Coach Bagshaw’s team. There was no officially recognized national football champion at that time. The Associated Press did not poll college coaches and crown champions until 1934. But Alabama, using various credible metrics has determined that the Crimson Tide and undefeated Dartmouth should be considered the 1925 co-champions. Furthermore, Alabama Public Television produced a fascinating documentary on the 1925 Alabama squad and their trip to the Rose Bowl. “Roses of Crimson” can be viewed on YouTube.

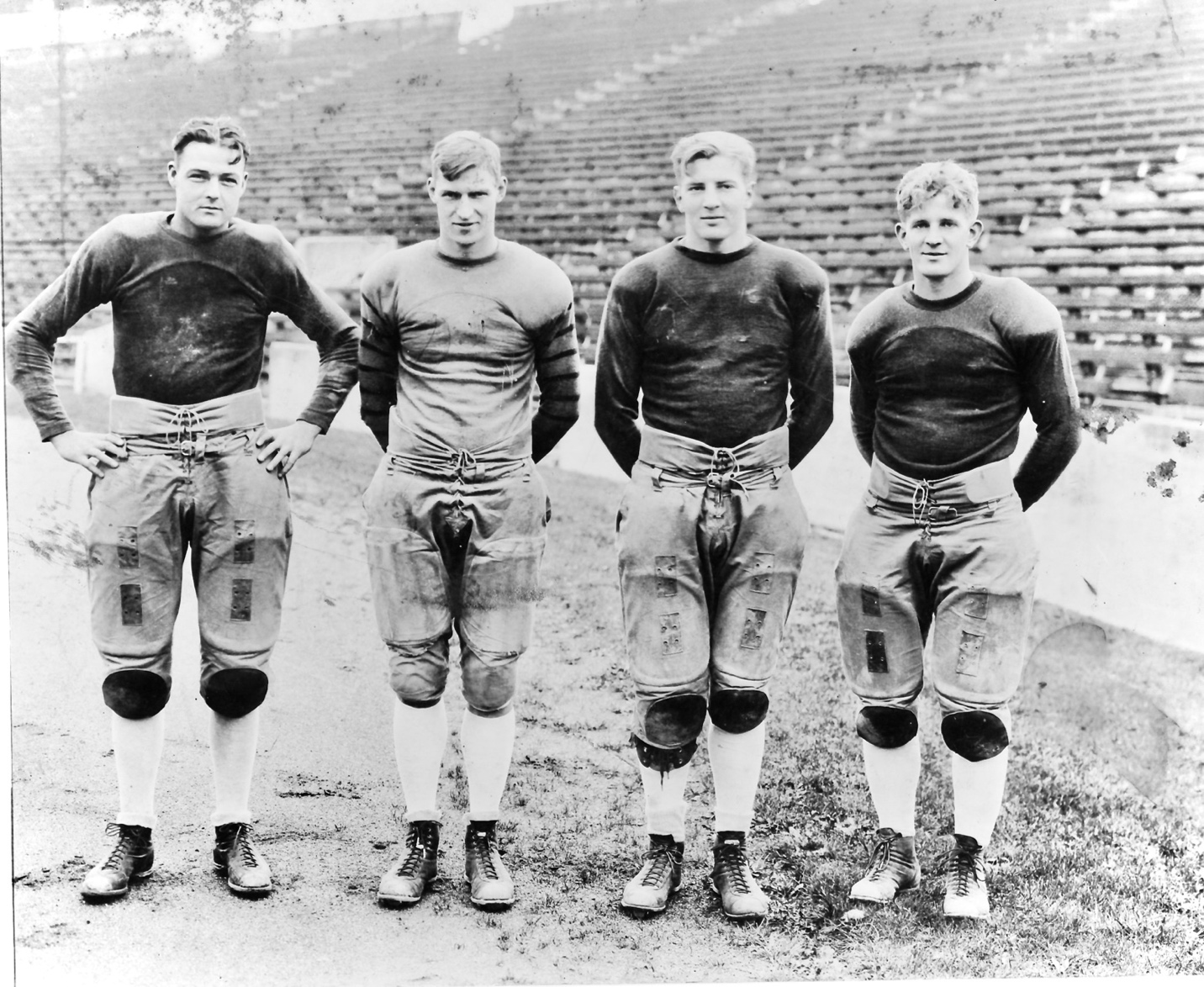

Four teammates and Beta Theta Pi fraternity brothers from Washington's 1925 PCC championship football team which lost 19-20 to Alabama in the 1926 Rose Bowl game: from left: Clarence Dirks (tackle), Leroy Shuh (end), Herman Brix (tackle) and Elmer Huhta (guard). Dirks became a Seattle Post-Intelligencer sportswriter and columnist. Brix was a silver medalist in the 1928 Olympics and starred in the movies as Bruce Bennett. Huhta became a legendary football and basketball coach at Hoquiam High School.

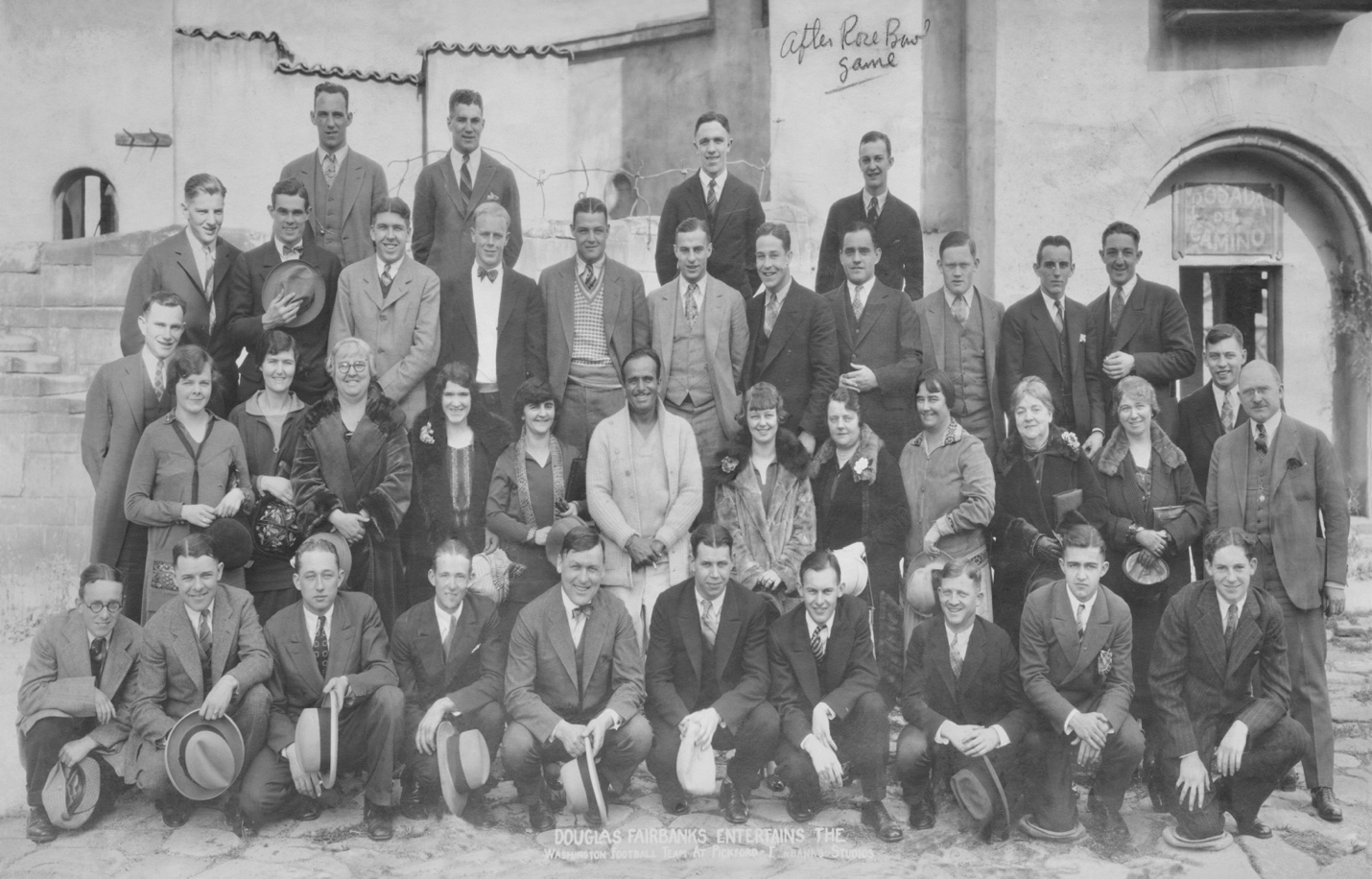

The Washington Huskies football team visits Douglas Fairbanks at his studio after the 1926 Rose Bowl game against Alabama. Clarence Dirks is behind Fairbanks and to the left. Head Coach Enoch Bagshaw is in front of Fairbanks and to the left.

Reluctantly, when the school year ended Dirks decided he needed to take a year off from his education to replenish his financial coffers. A ship building boom of sorts was taking place in New Jersey and my dad headed there for a year’s work as a ship caulker.

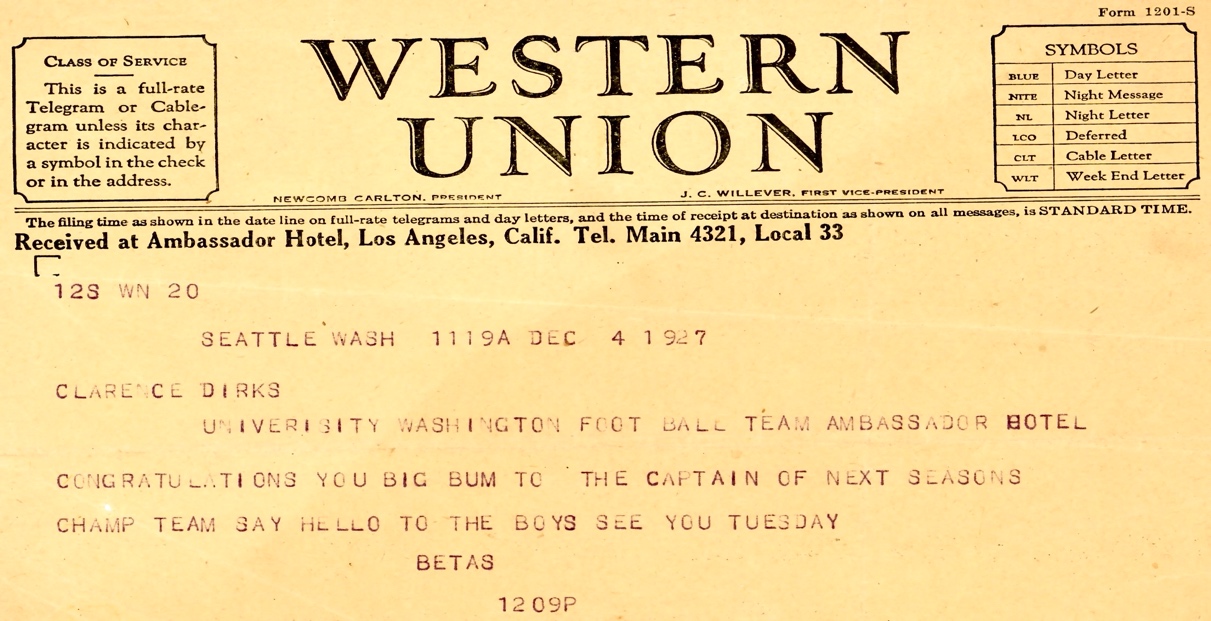

Back in Seattle, he re-enrolled at the UW with a healthier bank account and muscles well-conditioned after a year of hard labor in an East Coast shipyard. And he had his best year yet as a member of Enoch Bagshaw’s pigskin brigade. The team recorded a 9-2 record and Dirks was outstanding. While playing the final game of the season against USC in Los Angeles, he received a telegram from his fraternity brothers back in Seattle congratulating him on being chosen to captain the 1928 team.

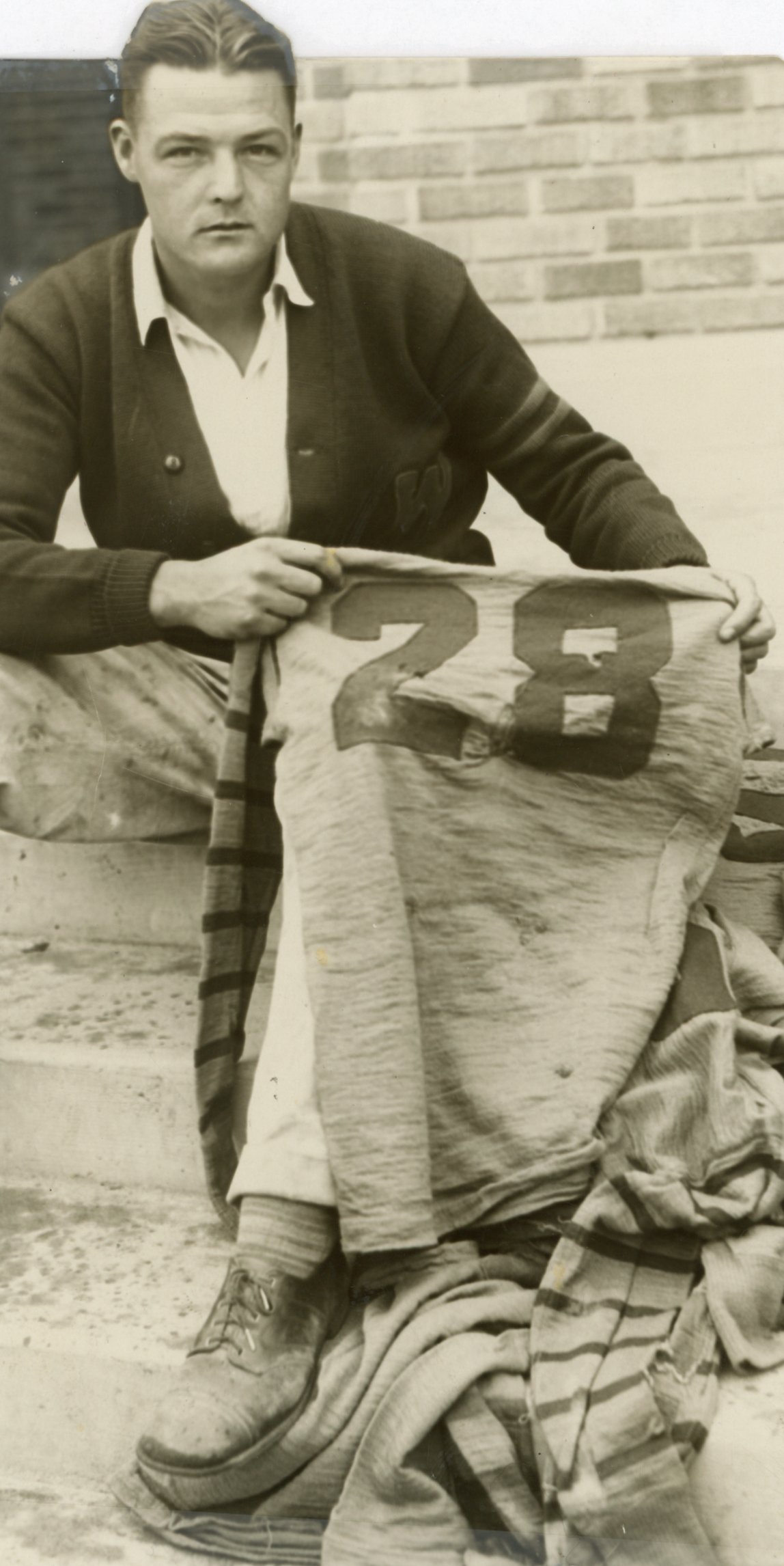

Clarence Dirks wore jersey number 28 in his three years on the UW football varsity: 1925 (reserve), 1927 (star), 1928 (captain). He skipped the 1926 season to work on a New Jersey waterfront. A fifth-generation ship caulker, he was the first in his family to attend college, probably the first to attend high school.

And Clarence Dirks received some national attention for his outstanding efforts as a tackle for Washington. The American Golfer magazine included him among 14 players it deemed players to watch, “Gridiron Warriors Who Lead,” as they put it. Aspiring All-Americans, 7 of the 14 did gain that elevated status at the end of the 1928 season. But Clarence Dirks was not among them.

Clarence Dirks was among 14 college football standouts and team leaders The American Golfer said to watch in its October 1928 issue. Half of the 14 made All-American status at the end of the season.

Unfortunately, 1928 was less than a banner year for the Huskies who ended with a 7-4 record, most of its wins coming against non-conference foes. Dirks himself suffered a broken bone in his leg at the start of the eighth game and only returned briefly in a 6-0 defeat of Washington State at the end of the season. Outstanding play from the UW’s second consensus All-American, Chuck Carroll (later a long-time King County Prosecutor), was the season’s bright spot. Coincidentally, Carroll, like Dirks in Palo Alto, was chosen by Seattle’s Garfield High School in 1950 as the school’s greatest all-time athlete.

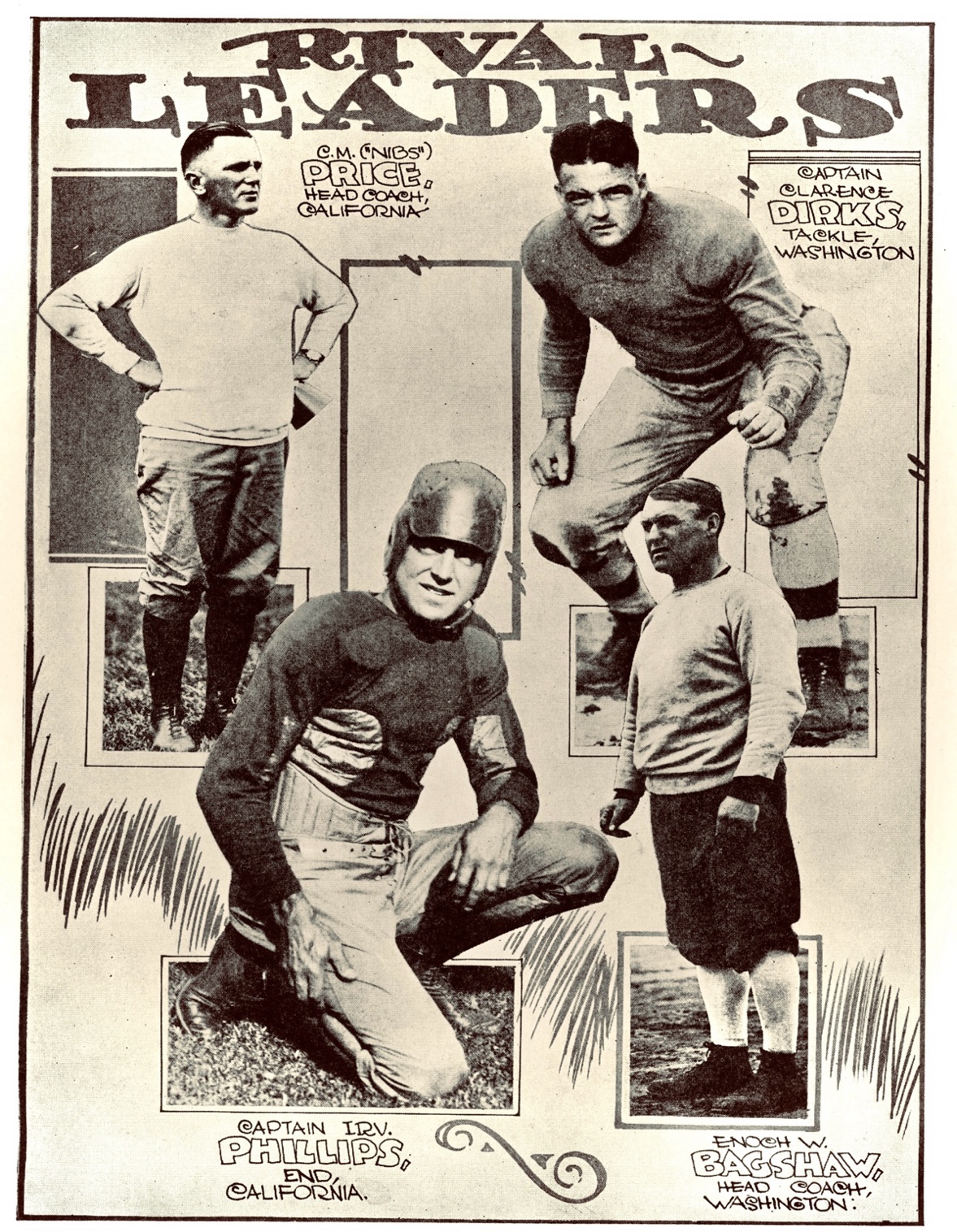

A page from the 1928 California-Washington football program.

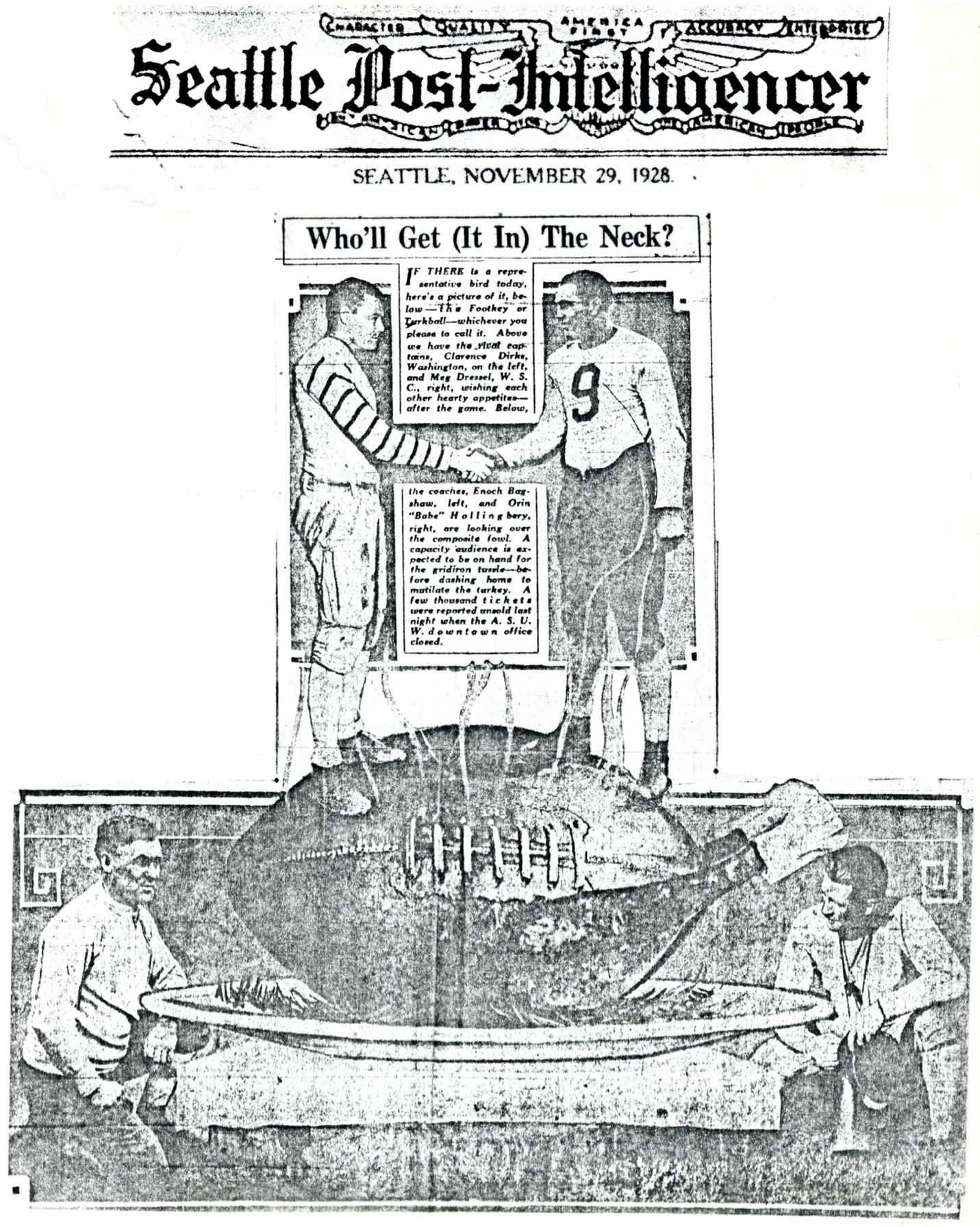

This somewhat bizarre photo greeted Seattle PI readers who opened the sprots section on Thanksgiving Day 1928.

While his football career ended that year, another career had just begun. Royal Brougham, then managing editor of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper, had hired Dirks as a student correspondent at the start of the football season and offered him a fulltime position at season’s end. With just one course to complete for his degree, my dad began his career as a by-lined sportswriter at the PI in February, 1929. His first articles included a photo of him in his leather football helmet.

This photo came from the PI Archives and shows how the original was cropped to use alongside Clarence Dirks' sports articles.

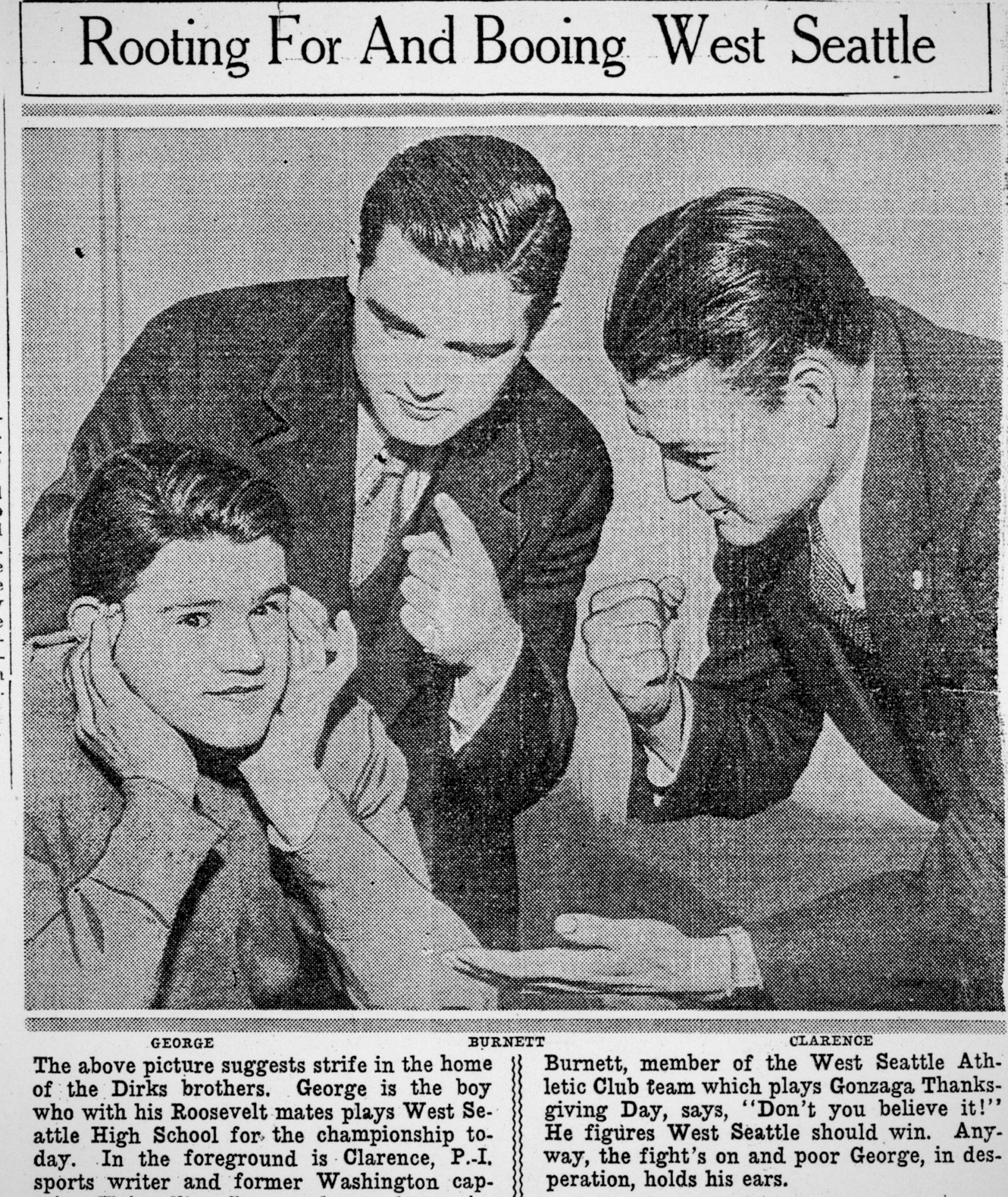

This photo appeared in the November 20, 1931 issue of the Seattle PI where Clarence Dirks was in his third year as a sports writer. Younger brother George’s time at Roosevelt overlapped with that of Joe Rantz, one of the 1936 UW oarsmen who won gold for the USA in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. George later attended the UW where he was a collegiate boxer before transferring to a California college. Burnett’s West Seattle Athletic Club team prevailed over Gonzaga University on that day in 1931 by a score of 13-12.

In the summer of 1930 Cleo Coons, who had just completed her freshman year as a UW journalism student, joined the PI staff as a summer intern. A year later she and Clarence Dirks were married.

Cleo Coons is shown standing to the right of the house mother (wearing a dark dress) in the front row in this Phi Mu sorority photo from 1930 or 1931. After just one year as a UW journalism student, she earned a summer internship at the Seattle PI where she met her future husband Clarence Dirks. As a sophomore she took playwriting classes and had one of her creations staged on campus.

The newly wedded journalists spent their honeymoon at the Indian Beach fish camp resort on Camano Island some 60 miles north of Seattle. That island would retain a special significance for the couple throughout their married life.

Clarence Dirks caught this 24-pound king salmon on his honeymoon with wife Cleo at the Indian Beach fish camp resort on Camano Island in the summer of 1931.

Clarence Dirks continued his Seattle PI career into the 1930s. By 1935 he was an established voice of the Seattle athletic scene. And like most sportswriters, he could be a bit of a cheerleader, especially where his beloved Huskies were concerned. But one thing was beginning to bother him: the lack of Black faces on UW teams. UCLA had them; Washington did not. Covering high school football championship games, Dirks had become well aware of the talent coming out of Seattle’s Garfield High School. And many of the school’s best players were Black. Why had Brennan King, he wondered, a multi-sport Garfield star, completed his college education at North Carolina A&T rather than the closer-to-home UW? Frustrated, Dirks did what little he could to remedy the situation. In 1968 Larry Gossett, later a longtime King County councilman, recorded an interview with a contemporary of Brenan King and summarized: “Charles Russell attended Garfield High School and UW, where he was noted as a star football player. He left the UW because of discrimination on the part of his coach, James Phelan and other team members. He was only allowed on the football team because of pressure, largely on the part of Clarence Dirks, a Seattle Post Intelligencer sportswriter. Russell left Seattle after 2 years at the UW…” At least Russell did earn a football letter before his departure. Clarence Dirks continued covering his local sports beat. It would take the Huskies two more decades before they achieved something closer to racial equity on the playing field.

The year 1936 proved a pivotal one for both Clarence Dirks and for Al Ulbrickson and his Husky oarsmen. While Coach Ulbrickson was preparing his crew for their final US races and money was being for their trip to Berlin, Dirks was preparing for a newspaper strike. He knew it would happen. As he told me 40 years later, “Every time Hearst got another load of marble from Italy for that damn castle of his, our pay packets got a little bit slimmer.” And you’ll recall, I’m sure,” from reading The Boys in The Boat, that just as the Husky Crew beat its opponents in dramatic fashion in Berlin, the PI’s reporters and staff did go on strike. The last straw was the firing of two senior staffers for joining The Newspaper Guild. Royal Brougham, in Germany with the UW team, was unable to file a story that would have been one of the most unforgettable he ever wrote.

Several months before the strike began, Clarence Dirks secured a second source of income, meager as it was. Sponsored by a Seattle clothier, he began a weekly sports program on KOMO radio. While mainly covering UW athletics, his most memorable broadcast occurred at a boxing match. Freddie Steele, known as the “Tacoma Assassin,” was defending his world middleweight title against challenger Eddie “Babe” Risko in Seattle’s Civic Stadium on July 11th. As a gimmick Dirks convinced the fight’s organizers to let him box a round with the champ and another with the challenger as a warmup before the main event. Dirks then told his radio audience what it felt like to get knocked to the mat by each competitor. He never received more mail after a single broadcast. And the event gave him a trifecta of sorts. Besides his radio coverage of the fight and his newspaper story the next morning, he wrote an article that appeared later in a national boxing magazine (“Fists of Steele,” Ring Magazine, November 1936).

The PI strike would last over three months. Clarence Dirks was feeling the pressure for extra income He not only had a wife and two-year-old child (Marty, UW’60) to feed, he and his wife had recently purchased an old Indian Beach cabin and lot where they had honeymooned from the elderly owners who had closed their resort. Payments had to be made and Dirks was determined to sell more magazine articles. The recent College Humor article “Varsity Log” had brought in $150 and the Esquire collaboration with Al Ulbrickson, “Row, Damit, Row” about the same. “Poughkeepsie Pluck,” in Dime Sports had paid less. Both “Varsity Log” and “Sweeping the Hudson,” another collaboration with Ulbrickson, had earlier been submitted to The Saturday Evening Post and summarily rejected. But Dirks was certain he could make a sale to that more prestigious publication. (Esquire was still a fledgling magazine at that point.)

Four weeks after Roosevelt beat Landon in the 1936 Presidential race, the Hearst Corporation settled with its workers at the Seattle PI giving Clarence Dirks a $10 a week raise and a five-day work week instead of six. And then a few days later a telegram arrived from the Saturday Evening Post. The article “Rockne of Rowing” based on interviews Dirks had conducted with Al Ulbrickson after his return from Germany had been accepted and a check for $500 was on the way. At last, a sale to the Post! The $300 balance owed on the somewhat dingy Camano Island cabin and waterfront lot could now be paid off in full. Some of the building materials for a more spacious vacation home could be purchased.

A slightly cropped version of this photo appeared with the Saturday Evening Post article "Rockne of Rowing” (June 19, 1937). The article described the legacy of early UW crew coach Hiram Conibear, the famous stroke he developed and how his groundwork eventually resulted in the Husky victory in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The photo caption read: “The Conibear Stroke in its Native Habitat. Washington Huskies on Lake Union.” Note the Alaska cannery ships in the background. (Photo by Art French, Seattle Post-Intelligencer)

Dirks now went to work in earnest writing magazine articles in his spare time. With increased confidence, he spent several evenings interviewing George Pocock, scholarly, internationally known builder of racing shells. The result, “One Man Navy Yard,” was sent to the Post. Eventually, a reply was received. The editors wanted to use the article but revisions would be needed. Another interview with Pocock took place, the article was re-submitted and shortly thereafter accepted with the promise of another $500 check on the way.

The cover of the June 25, 1938 edition of The Saturday Evening Post shows an artist's rendition of the University of Washington crew at work. Inside was the article “One-Man Navy Yard” by George Pocock and Clarence Dirks. Dirks used the $500 payment for his article to partially finance a cabin he was building on Camano Island.

This photo of George Pocock is from my dad's archives. A smaller version was included in the Saturday Evening Post article about Pocock's work and his philosophy as well as Hiram Conibear's influence on collegiate rowing. Here, Pocock is working in his shop in the ASUW Shell House.

A final sale to the Saturday Evening Post gave the Dirks family all they needed to complete their second home on Camano Island. Clarence Dirks loved to fish at Camano and he approached the Post about using an annual Seattle fishing derby as the focus for an article. The editors were only lukewarm about the idea but noted Dirks’ enthusiasm for the project and told him to submit the completed article for possible consideration. A more positive response was hoped for, but Dirks finally completed “Salmon Derby” and sent it in. To his surprise, it was accepted immediately.

With five thousand people jammed on the wharf of the West Seattle boathouse and overflowing into the street, salmon were weighed in for the Seattle Star-Ben Paris Salmon Derby. (Photo by Fred Carter, Seattle Star). This photo was one of several used in the September 7, 1940 Saturday Evening Post article

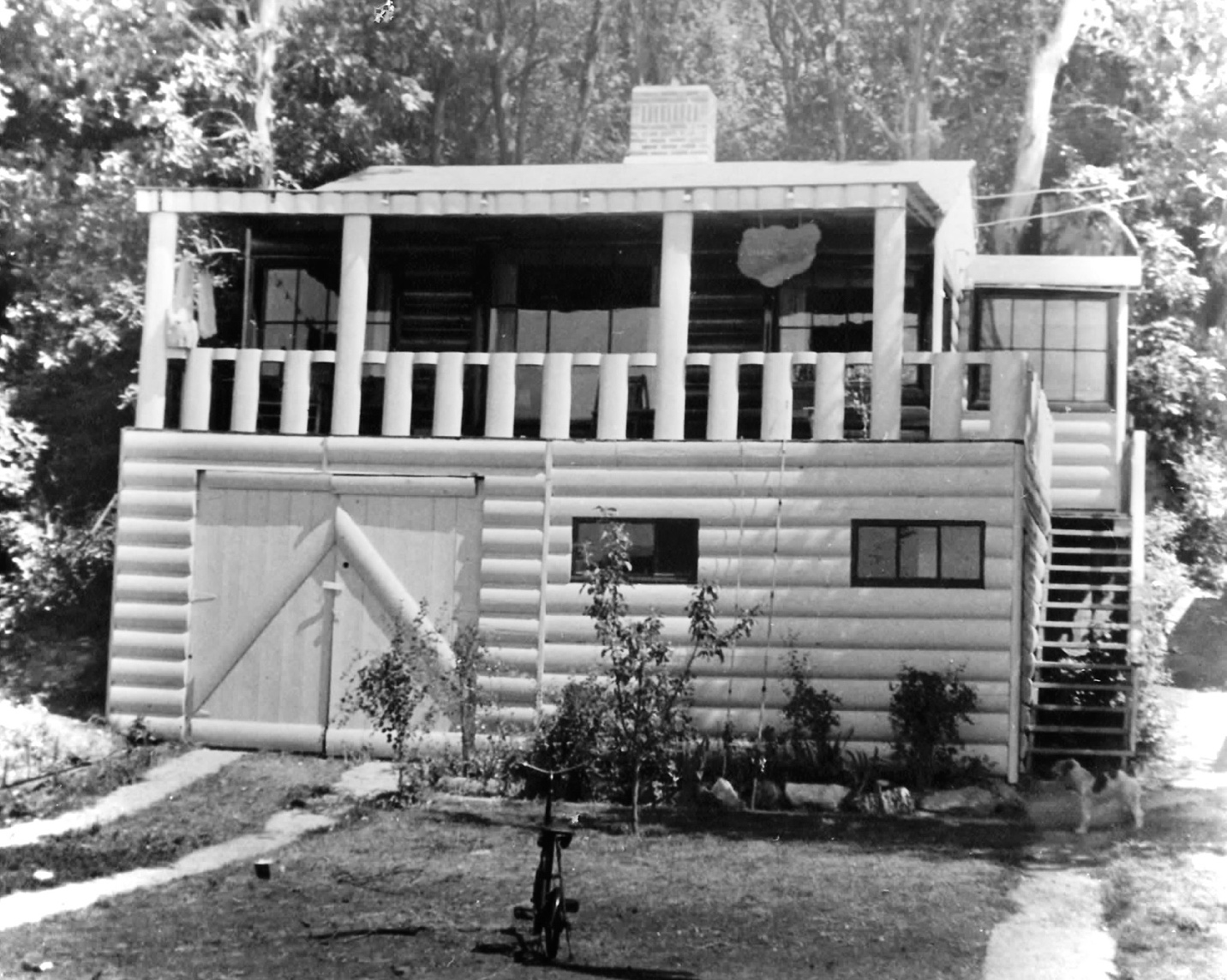

Finances in hand, Clarence Dirks, his father-in-law and several Indian Beach neighbors could now complete the cabin that resulted from the proceeds of half a dozen magazine articles most of which related to the University of Washington’s crew, its coach and the builder of its renowned racing shells.

This cabin at Indian Beach on Camano Island was financed by the sale of magazine articles by Clarence Dirks largely about the UW Husky Crew. Cleo Dirks, Clarence’s wife, wrote “The House the Post Built” (Writers Digest, July 1941) detailing the trials, tribulations and ultimate successes leading up to its construction. The article could have just as easily been titled “The House the Boys in The Boat Built..”

Clarence Dirks could now focus on his job at the Seattle PI, his family and fishing at Camano Island. But World War II soon intervened. The need for skilled workers at Seattle shipyards was evident and in May 1942 Dirks became a fulltime caulker on the Seattle waterfront after his workday writing sports stories ended. After six months he was exhausted. His last sports byline appeared in the November 2, 1942 edition of the PI with a story about an upcoming, crucial football game pitting his alma mater against UCLA.

But his career as a newspaper writer was far from over. At the conclusion of the war the Dirks family decided to sell their Seattle home and relocate to Camano Island. After a year in their cabin during which Clarence Dirks was unsuccessful at writing his version of the Great American Novel, they bought a small farm nearby and attempted to make a go of growing apples and holly, raising cows and chickens and keeping bees. I was born soon after the move. Visiting former colleagues from the PI later convinced my dad that he could make more money writing about his rural adventure than he would ever make from the farm itself. Thus, his column “The City-Bred Farmer on Puget Sound” was born. Within two years it went from one day a week to five. A morning radio broadcast on Seattle’s KOMO soon followed. Mention in one column that neighbors were in need of a church to replace an aging camp building they were using resulted in a campaign that funded its construction. And Clarence Dirks was becoming in demand as a speaker.

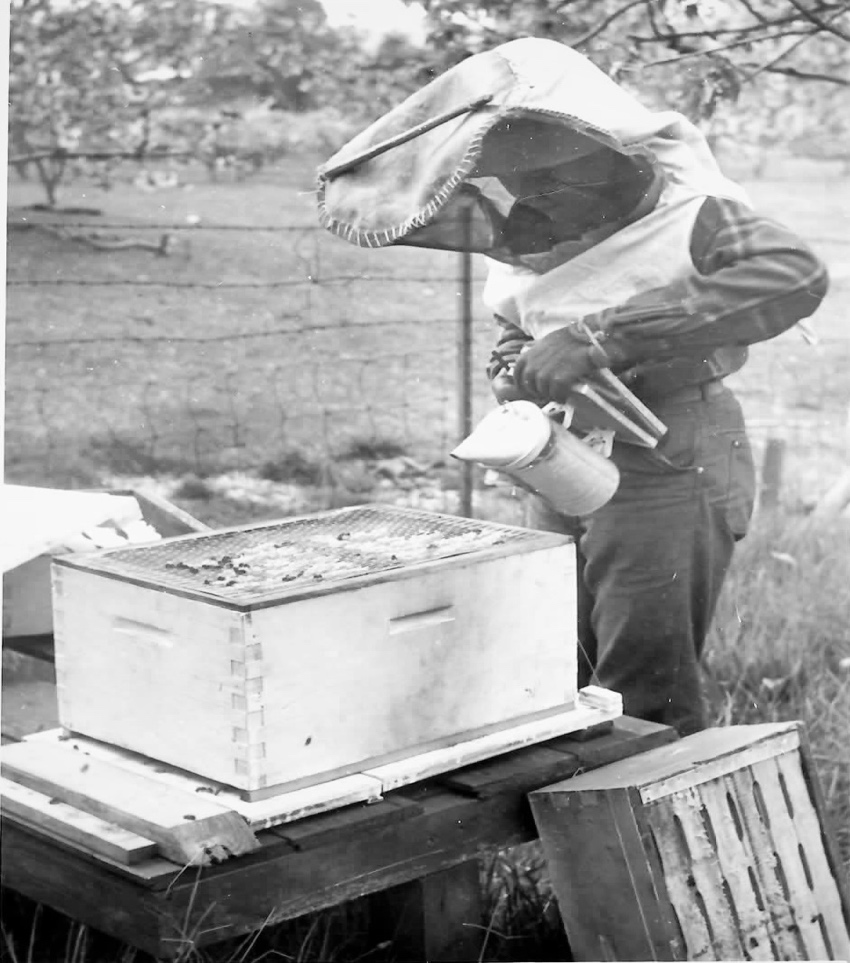

The City Bred Farmer, Clarence Dirks, is shown at work outside his new home on Camano Island. He has 18 acres filled with apple trees, milk cows, holly bushes and bees to tend in his new life away from sports writing deadlines.

Raising chickens presents new challenges for novice farmer Clarence Dirks. Collecting eggs each day is just a small part of the job. The Farmer is seen pondering his new responsibilities.

George Dirks, ship caulker and father of columnist Clarence, came up from California to lend a hand to the novice farmer. The elder Dirks was referred to as Grandpa George or GG in his son's column and had himself tried his hand a dairy farming some 40 years earlier in Palo Alto.

Marty Dirks, son of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer City Bred Farmer columnist, is learning the ins and outs of bee keeping. His new studies in agriculture also included the care and milking of dairy cows.

Camano Chapel volunteers are shown in front of their almost complete church in this 1951 Ken Harris photo. Farmer Clarence Dirks and Pastor Jerry Wheeler are seen going over the building plans with Marty Dirks standing behind them. Donations from readers of the City Bred Farmer column financed the chapel’s construction.

Unfortunately, the pressure caused by all these activities took a toll on the Dirks marriage which ended in 1952. A little over a year later my dad remarried. The column continued another six years.

After his Seattle PI job ended Clarence Dirks tried several other means of earning a living. He had become the lay pastor at Camano Chapel, the church funded by his column’s readers, and continued in that role for a decade. He wrote articles for a commercial fishing newspaper and worked for a time at the Anacortes American. He even tried his luck as a commercial fisherman. He ran unsuccessfully for the US Congress. Eventually he returned to the trade he learned decades earlier; he became a ship caulker again. But this did not keep him from writing. His last two articles to appear in the PI were about ship caulking. His August 15, 1965 piece was titled “When a Luxembourg Cook Tamed The ‘7 Wild Men’ of St. Michael: An Alaskan Adventure at the Mouth of the Yukon.”

Clarence Dirks caulking a river barge at St. Michael, Alaska. This photo accompanied his 1965 Seattle PI article.

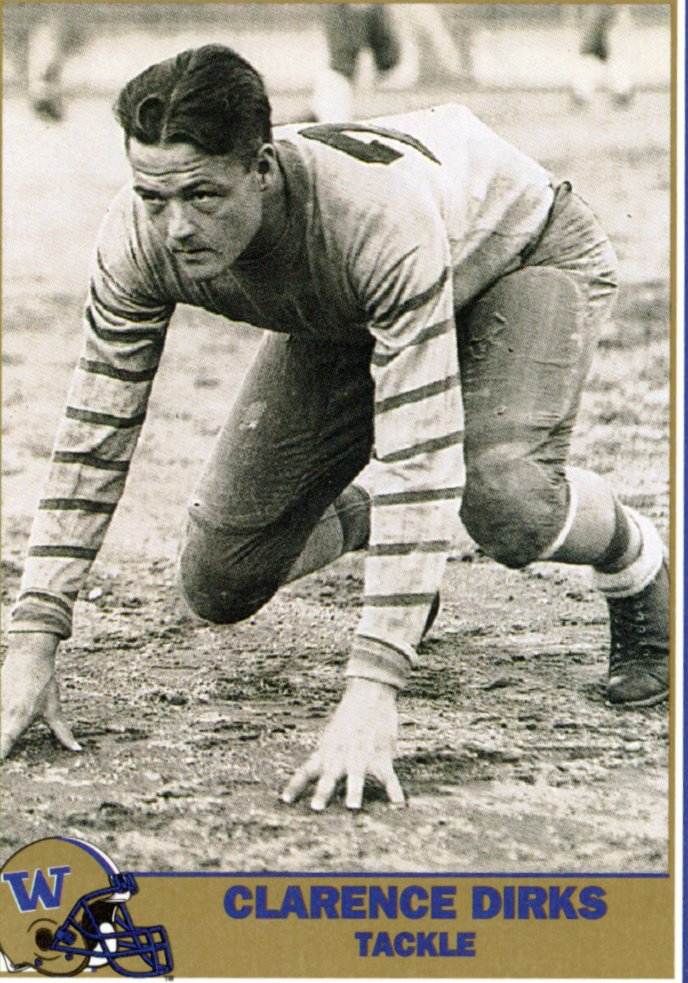

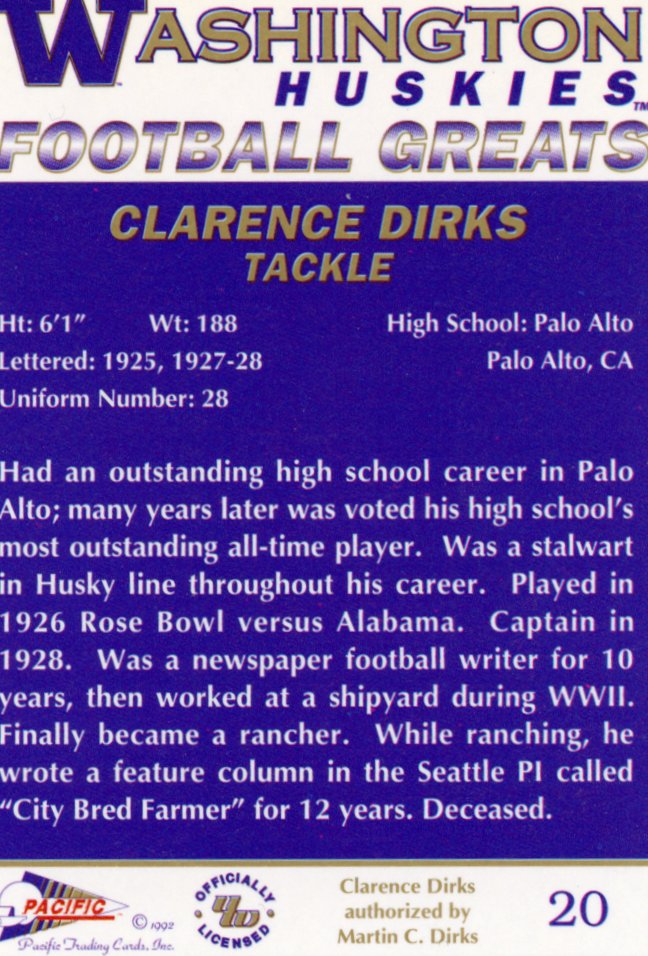

After his death in 1985 my dad received some of the recognition he richly deserved both as an athlete and as a newspaper writer. In 1992 he was included in a UW authorized set of sports cards ‘Washington Huskies Football Greats;” one of 100 players selected.

And in 2001 the church he had helped found held a 50th anniversary celebration. Camano Chapel had, by then, grown from a small congregation into a mega-church, the largest on Camano. As part of its celebration, it held a Clarence Dirks night. One parishioner played the part of my dad and read a dozen or so of his “City Bred Farmer” columns. One of these has always been a favorite of mine and I’ll conclude my tribute to my dad, always a proud UW alum, with it.

Farmer, Petunia in Football Match

(Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 7, 1948)

Ordinarily, in the early morning after milking, these lines are written before Cleo and Marty and little Michael are awake….

This morning, as the farmer sat down, he glanced outside, trying to snare a random thought.

Omigosh! Petunia, the pig, had gotten out of her stall! Petunia was in deep grass near the garage doors. She was eyeing the gate!

“Petunia?” asked Grandpa George as he waited for the milk to cool so it could be taken to the stand by the road. “Oh, the pig!”

The instant Petunia saw two lumbering 200 pounders bearing down on her, she emitted a startled grunt. She turned and took off in tall grass toward the calves’ pen.

“Remember the time Big Bill, the ram, broke loose and you had to tackle him in a patch of thistles,” warned Grandpa George. “If Petunia ever gets in the alley, you’ll never see her again.”

The Farmer chased Petunia like a bulky tackle going downfield under a punt.

Indeed, it was like the old football days all over again when Petunia reached the fence, whirled and faced the Farmer.

Petunia was like a half-pint ball carrier. She very well could have been little WSC star Butch Meeker, who used to stand, catch a punt, then watch the Farmer, among others, bear down on him.

Suddenly Butch would give his hips a little shake. The Farmer would go one way. Butch would go the other.

That’s precisely what happened now. Petunia flapped her ears to the left, squealed. As the Farmer dove, Petunia zigged to the right.

Sprawling on his stomach, the Farmer found nothing in his grasp except grass.

“Okay,” yelled Grandpa George, disgusted. “You missed her. She’s in the barn now. Go round to the side entrance so she can’t get out that way. I’ll go in this door. We’ll have her trapped between us.”

A long cement floor alley cuts through the barn. Stalls are on the left. Baled hay is stacked against the wall. In between is the alley.

The Farmer found Petunia perplexed in the alley as both exits were blocked. The big problem was now to try to catch her.

Grandpa George held a finger to his lips for silence. He bent down low, trying to slip up behind her from the back side of a bale of hay.

When Petunia eyed him, Grandpa George slipped to his hands and knees and commenced to crawl as little Michael used to do.

Suddenly, Grandpa George made a lunge. He missed her by inches.

Petunia started toward the Farmer, found her way blocked, turned and, with hard feet scratching the cement floor, commenced ear flapping around in a circle.

“I’ve got her!” cried the Farmer.

He thought he did. But Petunia’s fat little white-haired body squeezed through his hands. She ran between his legs, reversed her field, and dashed right into Grandpa George’s arms.

All Grandpa George had to do was grab and hold her by the hind legs.

How Petunia squealed!

After Petunia was back in her stall, Grandpa George said: “Now fix the door this time so she can’t get out.”

A wooden door soon replaced the two bales of hay….

Eggs collected 8.

Clarence Dirks, a Husky to the core, could never forget his time on the UW gridiron.

The author, Mike Dirks, is himself a proud UW alum (UW’68). Not an athlete like his dad, he does remember when, early in his freshman year, a member of the Husky Crew coaching staff stopped him outside the student union and suggested that he might want to try out for the team and offered him two-week trial period, room and board included. Flattered, but certain of the outcome, he turned him down. Mike Dirks got a degree in math and had a 47-year career as a high school and community college teacher.